Mohamed Amin, a Kenyan photojournalist, best known for drawing the world’s attention with photographs of Ethiopia’s famine in 1984 which inspired the Live Aid concerts, is now to be used as the face of NFTs that will raise funds for archiving African cultural work and history. Five of his images will be used to raise $250,000 in startup funds.

“What we found out is that there are very few archivists in Africa,” said Salim Amin, the son of Mohamed, who died in 1996 after his plane was hijacked and crashed in the Indian Ocean.

“We are losing so much of our history because nobody is really interested in putting it together.”

Salim and the Kenyan organization that bears his father’s name are pioneering the idea, which includes collaboration with famed African NFT artist Osinachi, whose work has sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A non-fungible token, or NFT, is a one-of-a-kind item (typically digital art) that is registered on a blockchain.

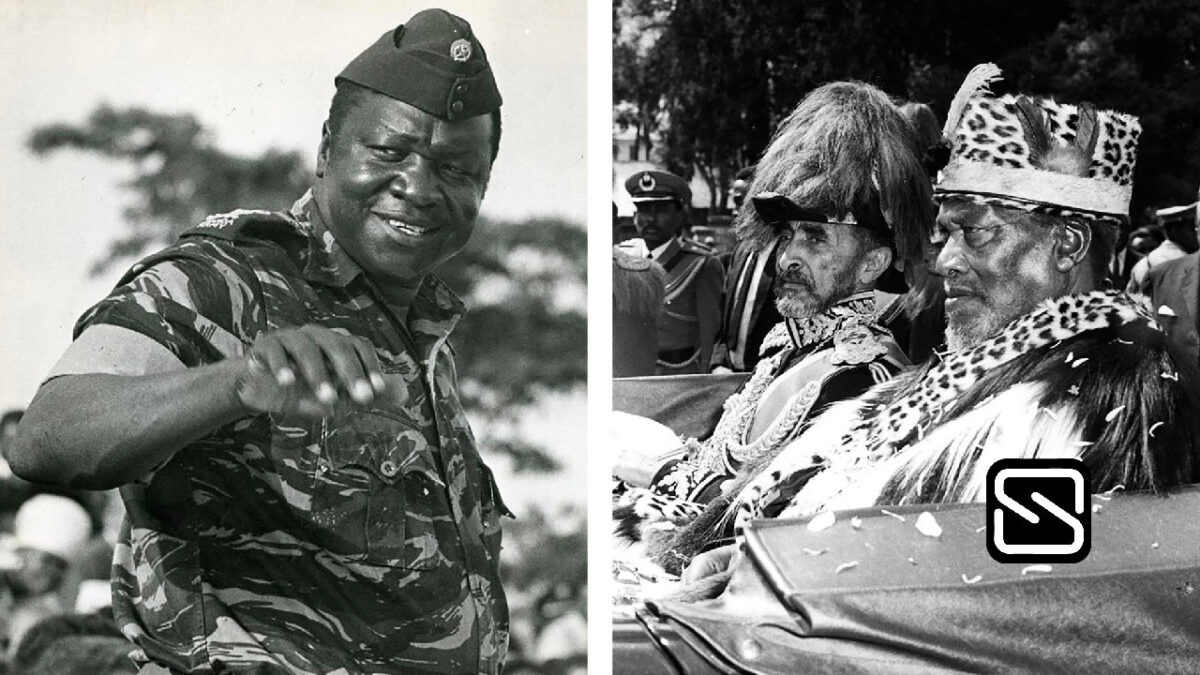

Mohamed photographed the wars and coups that accompanied the rise and fall of numerous African governments, as well as the continent’s cultures, flora, and animals, over the course of his decades-long career. While he is best known for documenting the Ethiopian famine, he lost his arm in an explosion while photographing the country’s civil conflict in 1991. He also spent a lot of time in the Middle East, traveling and working there.

“Funding from the NFT will be used to both preserve African history and teach people around the continent how to archive,” Salim said.

The 51-year-old is also working on a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) called AfrofutureDAO with Andrew Berkowitz, a web3 entrepreneur who co-founded online platform Socialstack. According to Salim, a portion of the profits from the initiative will go toward preserving the continent’s historical antiquities.

There are valuable items around the continent – including in museums owned by families – that are not archived and risk getting lost, according to Salim. “They don’t know what to do with it. It is just sitting in a box in the basement. So, we are hoping after we finish ours, we can go out there, collect, digitize and monetize it.”

“My long-term goal is to make it available for educational use, that can be given free of charge to every school in Africa,” Salim said.

Salim estimates that properly archiving his father’s work will cost around $3 million.